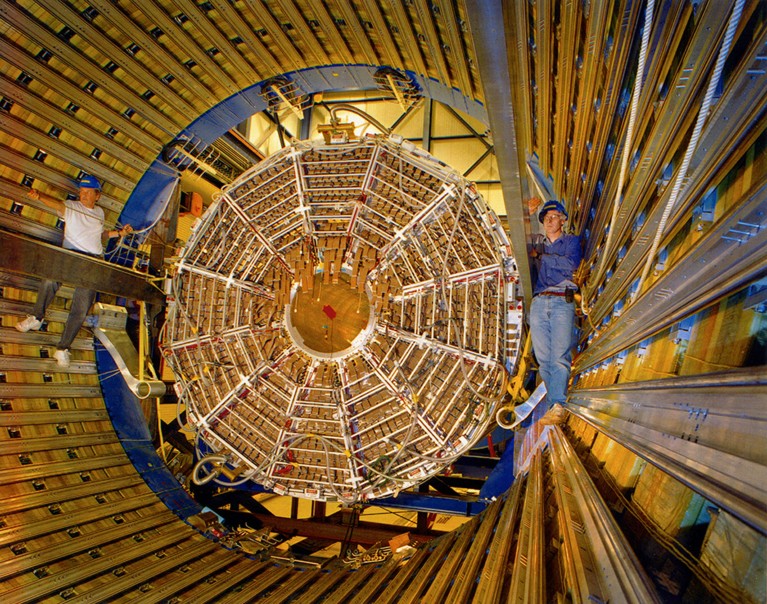

Contained in the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider’s STAR detector, which may observe the hundreds of particles produced when ions collide.Credit score: Science Historical past Photographs/Alamy

Physicists have discovered a brand new strategy to examine the form of atomic nuclei — by obliterating them in high-energy collisions. The tactic may assist scientists to raised perceive nuclei’s shapes, which, for instance, affect the speed at which parts type in stars and assist to find out which supplies make the most effective nuclear gas.

“The form of nuclei impacts virtually all features of atomic nucleus and nuclear processes,” says Jie Meng, a nuclear physicist at Peking College in Beijing. The brand new imaging methodology, revealed in Nature on 6 November, is “vital and thrilling progress”, he says.

Atomic nucleus takes two shapes

A crew on the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven Nationwide Laboratory in Upton, New York, collided two beams of uranium-238 — and later, two beams of gold — at excessive energies. They hit them “so laborious that we principally melted the nuclei right into a soup”, says co-author Jiangyong Jia, a physicist at Stony Brook College in New York.

The new plasma produced by the collisions expanded below strain very quickly, in a approach that was associated to the nuclei’s preliminary form. By utilizing a detector known as Solenoidal Tracker at RHIC, or STAR, to search out the momentum of every of the hundreds of particles created by each varieties of collision and matching the outcomes with fashions, the crew may “roll again the clock to deduce the form of the nuclei”, says Jia.

Hidden figures

An atomic nucleus is made up of protons and neutrons, which, like electrons, inhabit vitality shells. Typically, the particles tackle a form that minimizes the vitality of the system. Like a droplet of liquid, the nucleus can tackle quite a lot of shapes, together with that of a pear, American soccer or peanut shell. A nucleus’s form is “very laborious to foretell from concept”, says Jia. It might probably additionally change over time owing to quantum fluctuations.

Previous experiments exploring form concerned deflecting low-energy ions off the nuclei. This methodology — known as Coulomb excitation — excites the nuclei, and the radiation they emit as they fall again to the bottom state reveals features of their form. However the timescale is comparatively lengthy, so this type of imaging can provide solely a long-exposure shot exhibiting the common of any fluctuations in form.

‘The usual mannequin shouldn’t be lifeless’: ultra-precise particle measurement thrills physicists

In contrast, the high-energy collision methodology provides an on the spot snapshot of nuclei throughout influence. It’s a extra direct methodology, which makes it extra appropriate for finding out unique shapes, says Jia.

The approach confirmed that gold had an virtually spherical form that was constant from one picture to the following. By comparability, uranium modified throughout the snapshots because the nuclei collided in numerous orientations. This allowed researchers to calculate the relative lengths of its nucleus in three spatial dimensions, indicating that uranium shouldn’t be solely elongated, but in addition barely squeezed in a single dimension, like a deflated American soccer.

“I discover it fascinating that it labored” and that different nuclear processes didn’t affect the particle emission and obscure the deformation, says Magdalena Zielińska, a nuclear physicist on the French Different Energies and Atomic Power Fee close to Paris.

Laborious or mushy?

This sort of imaging may assist with the difficult process of distinguishing between nuclei which can be ‘inflexible’, with well-defined shapes, and ‘mushy’ fluctuating ones, says Zielińska.

Jia says his crew would additionally like to use the strategy to review the variations between lighter ions, akin to oxygen and neon. Oxygen nuclei are almost spherical, whereas neon nuclei — which carry an additional two protons and two neutrons — are thought to bulge out. Evaluating their shapes would permit researchers to know how protons and neutrons type clusters within the nuclei, says Jia.

Details about form also can reveal whether or not nuclei are more likely to work together or bear nuclear fission, and might increase the prospect of detecting a course of known as neutrino-less double β decay, which may assist clear up some long-standing mysteries in physics. Some 99.9% of seen matter resides within the centre of the atoms, says Jia. “Understanding the nuclear constructing block is principally on the coronary heart of the understanding who we’re.”