Knowledge evaluation by Kae Petrin

Join Chalkbeat Chicago’s free every day publication to maintain up with the most recent schooling information.

When Illinois lawmakers carved up Chicago into 10 areas for the metropolis’s first college board elections, one of many districts they created is a sprawling expanse that hugs town’s south lakefront from Soldier Discipline to the Indiana border.

District 10 has bustling high-performing faculties and shrinking campuses blocks aside. It has vacant buildings left behind from college closures and one of many highest common pupil poverty charges within the metropolis. However additionally it is residence to a lot of Chicago’s political and enterprise movers-and-shakers, together with former President Barack Obama.

The primary candidates to declare their bids for Chicago’s new, partially elected 21-member board have been in District 10.

Forty-seven Chicagoans — together with 10 in District 10 alone — tried to run for college board. However simply 4 made it on the poll right here: Robert Jones, a pastor supported by the Chicago Lecturers Union who as soon as joined a starvation strike to maintain a neighborhood highschool open; Karin Norington-Reaves, a nonprofit CEO and mom of a blind CPS pupil who had run for Congress and received backing from pro-school alternative tremendous PACs; Adam Parrot-Sheffer, a CPS mum or dad, former district principal, and schooling guide; and Che “Rhymefest” Smith, a self-funded Grammy Award-winning rapper and activist.

Over the next six months, what performed out in District 10, in some ways, mirrored the dynamics and drama of the historic race throughout town.

On one hand, the election was a joyful, uplifting train in illustration — breaking with a long time of mayoral appointments to a principally rubber-stamp college board. On the opposite, the messiness of democracy was on full show, with reductive, deceptive soundbites and massive money flowing into the races. It was powerful for newcomer candidates with out institutional backing or private wealth to hitch the race, together with the six individuals knocked off the poll in District 10.

Greater than $9 million was spent on mailers, adverts, and textual content messages praising or savaging the candidates, in line with a Chalkbeat evaluation of the most recent marketing campaign reporting. Nonetheless, many citizens went into the poll field on Election Day not figuring out that the varsity board race was even occurring.

As the brand new college board gears as much as take over in January and set requirements for a type of authorities new to Chicago, what are the teachings of town’s first ever college board elections? And what, if something, must be modified earlier than voters decide college board members once more in 2026?

‘A horrible option to do democracy’

In early September, 9 weeks earlier than the Nov. 5 election, Che “Rhymefest” Smith sat on the abandoned higher degree of the Subterranean, the Northwest Aspect music venue the place he’d reduce his tooth as a rapper again within the Nineteen Nineties. He was checking in along with his companion, Heather, and marketing campaign supervisor, Sean Tenner, earlier than a live performance to drum up help and lift cash for Smith’s college board bid. The Smiths and their music studio had already loaned the marketing campaign practically $100,000.

That night, Smith, who unsuccessfully ran for alderman in 2011, felt pissed off with this newest foray into campaigning. He railed about “the transactional nature” of Chicago politics.

He needed to speak about issues like cracking down on wasteful district spending or putting partnerships with museums and nonprofits to spice up arts schooling. However as he met with organizations whose endorsements maintain sway with voters, they solely appeared to care whether or not a candidate had a path to victory. His self-funded marketing campaign appeared to be a turnoff; it made it tougher to purchase his loyalty, he suspected.

He was additionally nonetheless shaken by the expertise of getting on the poll.

First, would-be candidates needed to safe 1,000 signatures — a threshold some elected college board advocates mentioned was prohibitively excessive. In all, 47 overcame that hurdle. However then 27 of them ran up towards a frightening and bewildering staple of Chicago’s elections: petition challenges.

The Chicago Lecturers Union paid a set of election attorneys to symbolize individuals difficult petitions in 18 of the circumstances, together with 5 in District 10. Smith and Norington-Reaves have been among the many candidates challenged by CTU proxies. The union additionally paid to fend off challenges to their endorsed candidates, together with District 10’s Robert Jones.

Smith challenged different candidates too, together with Jones. After a month of hearings and a overview by handwriting specialists, the 2 quietly agreed to drop their challenges towards each other.

The last-minute truce rattled Norington-Reaves, who amassed greater than 300 pages of voter affidavits and different proof to counter three challenges. She fired off a livid press launch, saying the race had been “marred by those that declare to help consultant authorities however undermine it in the identical breath.”

Smith was relieved he had made it. However he felt uneasy concerning the unsavory apply of making an attempt to knock out the competitors.

“It’s a very horrible option to do democracy,” Smith mentioned in a September interview with Chalkbeat. “All of us get caught up in a tangled net of the political course of.”

However that night time, Smith brightened as he headed downstairs to kick off the efficiency. In a black baseball hat, black-framed glasses, and a white “Rhymefest for CPS” T-shirt, Smith instructed the group that the varsity board controls every little thing from what children eat for lunch to how officers spend a $10 billion funds.

“These members would come from particular pursuits, enterprise,” he boomed on the mic, to a rumble of disapproval. “They didn’t actually come historically, traditionally, from our communities.”

‘Very low down on the poll’

A few weeks later, on an overcast Sunday afternoon in late September, Norington-Reaves strode down a quiet residential avenue on the far South Aspect, glancing at a cellphone app the place orange dots represented the 200 probably voters she hoped to succeed in that day with a pair of staffers and a small group of volunteers.

She’d performed this earlier than in a high-profile race for Congress and was prepared with a sophisticated doorstep spiel.

When an 80-something man opened his door, Norington-Reaves began chatting about her expertise as a bilingual Educate for America educator in Compton, California, earlier than a profession as an legal professional and a Chicago workforce growth official. She spoke about how she was impressed to run by her expertise making an attempt to line up college district providers for her daughter, a high-achieving pupil born with out eyes.

“If this was arduous for me, what’s it like for the common mum or dad who doesn’t have every little thing I’ve?” she instructed the person.

However the man, a retired trainer, was confused. Didn’t the mayor appoint the varsity board?

“How do you vote for members of the varsity board?” he requested.

Norington-Reaves had already participated in a dozen neighborhood boards concerning the college board elections and stuffed out quite a few candidate questionnaires. She’d spent eight hours or extra knocking on doorways each weekend. Chicago’s college board was within the information lots due to a push by the mayor and lecturers union to oust the district CEO. Regardless of all that, amid the high-pitched noise of a presidential election yr, most voters she spoke with nonetheless didn’t know concerning the college board race.

She defined to the person that the mayor would not decide all of the board members. By 2027, all can be elected.

“It’s very low down on the poll,” she mentioned. “I’m No. 103.”

“I promise I’ll vote for you,” the person mentioned.

Marketing campaign money flowed into the races

By early October, cash was flowing into and out of faculty board candidate marketing campaign coffers. At that time, the CTU was among the many largest spenders, serving to their endorsed candidates with area employees and different in-kind help. Then the Illinois Community of Constitution Colleges unleashed a half one million {dollars} to help individuals who favored college alternative — doubling all spending to that time. Spending solely ramped up from then on.

Jones, the pastor at Bronzeville’s Mt. Carmel Missionary Baptist Church, grew to become one of many candidates citywide with the most important struggle chest, because of the CTU. He had related with lecturers union leaders in 2015, throughout a 34-day starvation strike he’d joined spur of the second to maintain Dyett Excessive Faculty open. Now on the marketing campaign path, he typically introduced up the strike and echoed key union priorities, resembling increasing college staffing and a program referred to as Sustainable Group Colleges, wherein campuses get additional funding to crew up with nonprofits and increase after-school packages, household engagement, and extra.

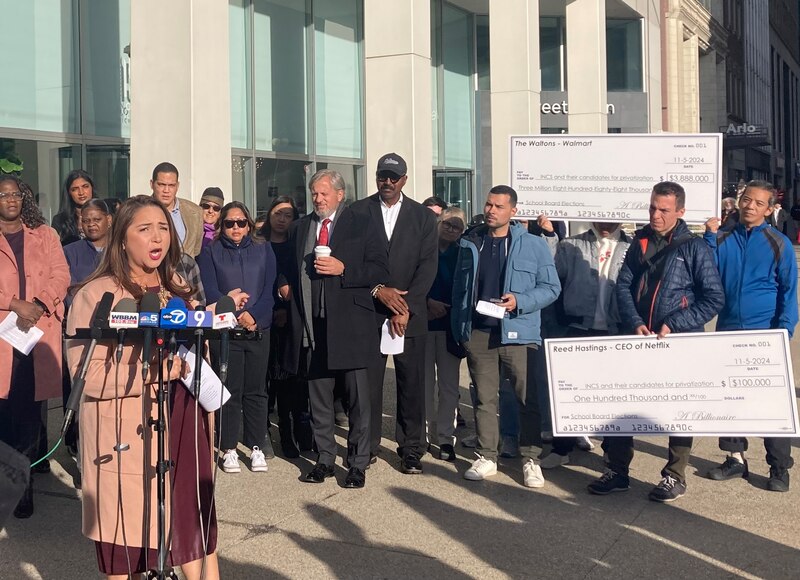

On a heat late October morning, he stood on the sting of a semicircle of elected officers, advocates, CTU members, and fellow college board candidates on a busy avenue within the Loop. The union had organized a press convention in entrance of the workplaces of the Illinois Community of Constitution Colleges to decry college board marketing campaign spending by the group, fueled by giant checks from rich individuals in and outdoors of Illinois. They have been calling for brand spanking new marketing campaign finance limits.

On the occasion, State Sen. Robert Martwick, an architect of the 2021 regulation that green-lit an elected board in Chicago, vowed to push for such laws, maybe modeled on cities the place candidates solely obtain a restricted quantity of taxpayer funding to marketing campaign. He acknowledged a method of ushering in an elected board — and leaving the small print on how it could be elected for later.

The earlier week, Jones’ opponent, Norington-Reaves, had discovered a shiny flier in her mail that includes a faceless marionette in a swimsuit and tie, together with the message, “Donald Trump and out-of-state billionaires are pulling the strings of Karin Norington-Reaves.” She’d laughed. She was a lifelong registered Democrat who ran for Congress as a Democrat with then-outgoing Congressman Bobby Rush’s endorsement. To not point out she thought-about Trump “essentially the most vile particular person in American political historical past.”

The deceptive mailer was paid for by the CTU, which justified it based mostly on the $250,000 spent by the Illinois Community of Constitution Colleges and one other tremendous PAC to help Norington-Reaves. These tremendous PACs can pump limitless {dollars} within the race so long as they don’t coordinate with the candidates.

In the meantime, Jones additionally bristled at fliers that took his marketing campaign supplies and swapped out his picture for the mayor’s, warning voters he was working to do Johnson’s bidding. The CTU’s backing was essential to his marketing campaign. The union had introduced in his area organizer, Abierre Minor, who pushed out textual content messages to voters and supporters with sign-ups for cellphone banking and canvassing. Greater than 40 volunteers had signed up. However Jones felt he was his personal candidate, a longtime supporter of labor that labor was now supporting again.

That October morning, Jones stepped as much as the mics. He spoke about his participation within the Dyett starvation strike. Then, glancing at notes, he mentioned, “Our youngsters usually are not on the market. Our faculties usually are not on the market. Our metropolis just isn’t on the market.”

Give attention to college students blurred by soundbites

Per week later, on a cool, cloudless Sunday morning, Parrott-Sheffer stood by the parking zone of the Southside YMCA in Hyde Park, an early voting website. When potential voters approached, he and a number of other marketing campaign employees for his opponents closed in. He pressed his marketing campaign bookmark into their palms.

“Adam Parrott-Sheffer, Kenwood Academy mum or dad, 20-year educator, hoping to earn your vote,” he rattled off as some strode by briskly.

In March, Parrott-Sheffer grew to become the primary candidate throughout town to file marketing campaign finance paperwork. Since then, he had tried to be all over the place. He attended college registrations, parades, mornings on the farmers market. He sat on 21 college board candidate panels, stuffed out 25 questionnaires, and frolicked on social media, “an previous man studying lots about TikTok.” He felt strongly the board wanted extra dad and mom and seasoned educators like him.

Nonetheless, Parrott-Sheffer knew he was a long-shot candidate. He’d by no means run for workplace earlier than and was handily outspent. He’s additionally a white man who was working for workplace towards three Black opponents in a predominantly Black district in a segregated metropolis whose political dynamics have been traditionally formed by race and ethnicity.

As Election Day approached, increasingly voters had requested the place Parrott-Sheffer stood on the mayor. The whole college board had resigned below strain to fireplace Martinez, the district CEO. Then, only a week after Johnson hurriedly hand-picked a brand new board, its new president resigned over antisemitic and misogynistic social media feedback.

The drama was not enjoying effectively with dad and mom and taxpayers, Parrott-Sheffer thought. It was giving non-CTU endorsed candidates like him a lift — however not that morning outdoors the YMCA.

A middle-aged girl dressed up in a pink jacket and lengthy white skirt stopped to listen to his spiel. Parrott-Sheffer began speaking about beefing up providers for college kids with disabilities and English learners, the significance of constructing positive college students can study by third grade, and the necessity to repair the district’s growing old college buildings.

The girl nodded approvingly after which reduce him off: “Are you working with Brandon Johnson?”

“I’m not working with Brandon Johnson,” he instructed the voter that morning. “I’m an impartial candidate.”

She pulled again and frowned: “Why are you not working with him?”

Is that this what democracy seems to be like?

The District 10 candidates greeted Election Day with a mix of hope, pleasure, and unease.

Parrott-Sheffer felt he had given a sturdy marketing campaign his all. It simply saddened him that at a time when the varsity district confronted a management and monetary disaster, the complicated, nuanced schooling problems with the day have been conflated to neat soundbites, a nifty dichotomy: Have been you with the mayor and his associates on the CTU? Or have been you with the constitution individuals, which made you a Trump puppet, regardless of the customarily bipartisan nature of each help and scrutiny of those faculties over time?

Smith felt his bid to solid himself as a changemaker had resonated with voters at a time of flux, even because the media and opponents hadn’t at all times taken him significantly. Norington-Reaves was worn out from months of juggling campaigning, a demanding job and motherhood, but additionally energized by honing her voice on the marketing campaign path. Jones had misplaced two belt loops door-knocking and speaking to voters, leaving him feeling extra related to his South Aspect neighbors.

It could take till the Friday after the election for the Related Press to name the District 10 race for Smith, one of many closest within the metropolis. He led with about 32% of the vote, to Norington-Reaves’ 29%. Jones got here in third, and Parrott-Sheffer fourth.

As of Thursday, Norington-Reaves had not conceded, noting that 1000’s of mail-in and provisional ballots are nonetheless being counted. She has additionally threatened to sue the Chicago Board of Elections over points in District 10 and others the place election judges handed some voters ballots for the improper college board districts.

The Chicago Board of Elections has acknowledged the problem however insisted it was mounted rapidly and chalked it as much as human error. In spite of everything, the varsity board races have been new, and the electoral district boundaries drawn by state lawmakers six months earlier didn’t align with preexisting precincts and wards. However Norington-Reaves says the issue took hours to deal with in some precincts. “Doubtlessly 1000’s of voters have been disenfranchised,” she mentioned the Friday after the election.

Throughout town, candidates endorsed by the CTU — famed nationally for its means to place boots on the bottom and end up voters — confronted a surprisingly uphill battle. Three out of the 9 who had aggressive races prevailed, becoming a member of one, Jitu Brown, who ran unopposed, on the brand new board. Three candidates backed by the constitution community received their races, and so did three independents — all on the South Aspect.

Cash had mattered throughout town — to a degree. In District 10, Smith spent about $5 and Parrott-Sheffer spent roughly $6 for every vote they’d earned, based mostly on marketing campaign finance information as of Nov. 12 and whole votes counted as of Nov. 14. Norington-Reaves and teams spending on her behalf had spent about $20 per vote whereas Jones spent virtually $27 per vote.

In keeping with the Chalkbeat evaluation, the CTU and a number of other allied teams largely funded by the union spent about $2.3 million. The constitution community and City Middle tremendous PACs spent roughly $3.5 million.

Longtime elected college board champions say town should reckon with the ups-and-downs of the races forward of 2026. Natasha Erskine, who leads the nonprofit Increase Your Hand, which noticed poll petition hearings, believes the signature threshold needs to be lowered. The hearings have been an train in “the Chicago approach,” with some well-qualified candidates booted and people with extra assets having fun with a transparent edge.

The nonprofit, which fought for an elected college board for years earlier than the state regulation was handed, hosted “mini teach-ins” earlier than its candidate boards to coach them about what the varsity board truly does. It needs to see extra dad and mom and seasoned native college council members run. It additionally helps setting some limits on large marketing campaign spending.

“We have been anticipating it however, man, we weren’t anticipating that,” Erskine mentioned.

State Rep. Ann Williams, a sponsor of the elected college regulation, mentioned voter consciousness and pleasure concerning the election did rise over time, making the varsity board “the new race” on the poll. She felt it featured many candidates desirous to have substantive conversations concerning the points — however who struggled to not be pigeonholed. Ellen Rosenfeld, a candidate backed by Williams, criticized the mayor and CTU but additionally put out a launch distancing herself from the pro-school alternative cash spent on her behalf.

Williams feels the poll threshold is true, noting that it’s going to change into 500 signatures in 2026 when the ten districts change into 20. She and different lawmakers are open to proposals to finetune the method.

Within the meantime, Johnson is poised to nonetheless maintain sway over the varsity system as he should now appoint 11 members to the 21-member board by Dec. 16. However 5 newly-elected members are asking the mayor and his present board to train restraint by not taking any main actions till the brand new board is seated.

Within the days after the vote, Smith referred to as the opposite two impartial winners, Therese Boyle and Jessica Biggs. They wanted to band collectively forward of January, he instructed them.

Becky Vevea contributed to this report.

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter overlaying Chicago Public Colleges. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.